How do you like your innovation? Incremental or disruptive? Evolutionary or revolutionary? Focused on growth or on game change? Since this paper was originally published two years ago BOLTGROUP has continued to help clients select the best strategy and create the right innovation. Sometimes the right answer has been transformation, other times redirection. But every time it required creative thinking, advocacy for the people who’ll use what we design, and diligence to bring the innovation to fruition.

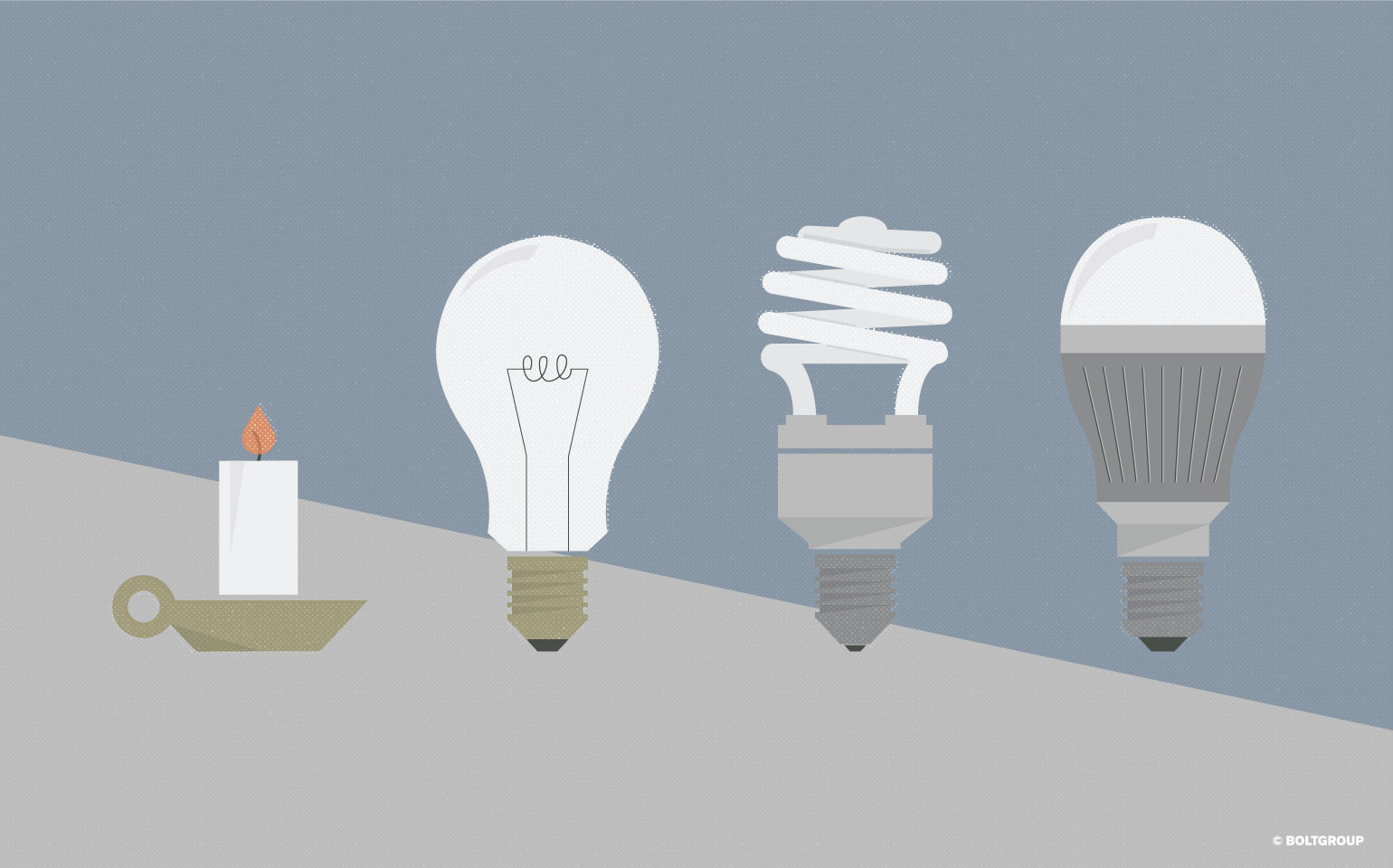

Business leaders yearn for “disruptive innovation”—that groundbreaking invention that revolutionizes markets and lifestyles. But most innovation is less dramatic. “Evolutionary innovation” can be every bit as valuable, and a lot less costly. In fact, smaller evolutionary innovations can have more influence than radical ones because consumers adopt them more readily. And evolutionary innovation may lead to disruptive innovation (for a surprising example, see #9 below).

But many mid-sized manufacturers don’t evolve their products in a way that results in meaningful innovation. Rather their innovations default to minor incremental improvements. This type of product development often won’t deliver meaningful levels of impact to the market or the business. This white paper explores examples of high-impact evolutionary innovation.

Evolutionary vs. Revolutionary Innovation

James Fahey, executive consultant to early stage innovators, says revolutionary innovation seeks to adapt the world to new ideas, whereas evolutionary innovation seeks to adapt new ideas to the existing world. Let’s compare.

Revolutionary Innovation

Revolutionary innovation is sexy. The concept of disruptive innovation, foretold by Clayton Christiansen, has the potential to spike growth, change human behavior, and create billionaires. Revolutionary innovators like Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, and Jeff Bezos have changed the ways we live, and built business empires in the process.

Evolutionary Innovation

Evolutionary innovation may be less sexy and more incremental, but it’s also less expensive, less risky, and more readily adopted by end users. “Fast followers” often succeed where the original inventors don’t. The Japanese have been wizards of this style of evolutionary innovation, but now companies around the world are doing it.

The Pioneer Advantage, Marketing Logic or Marketing Legend?

A study published in the Journal of Marketing Research illustrated the success rates of Fast Followers verses “First Movers”. The survey included 500 brands in 50 categories and showed that First Movers, the first to sell a product, had a 47% failure rate. Fast Followers, those that entered the market early, but not first, failed only 8% of the time. Why do fast followers win more often?

First Movers tend to launch without fully understanding customer needs and with little awareness of the technical and market hurdles in store. Fast Followers can take time to study the customer, learning from the First Mover’s mistakes, such as product development potholes. Plus, the market has been primed by the First Mover’s products in the market.

There are exceptions, especially in bioscience and pharmaceuticals. Here huge investments in R&D and marketing increase pressure to be first and improve the likelihood of success. But most often the smart position is to be a Fast Follower, building on past success—yours and your competitors. Here huge investments in R&D and marketing increase pressure to be first and improve the likelihood of success. But most often the smart position is to be a Fast Follower, building on past success—yours and your competitors.

High Impact Evolutionary Innovation

So how do mid-sized manufacturers create high impact innovation that will stave off competition and grow their business while avoiding risks of the “bleeding edge?” How do they create innovations that are desirable and valuable without the costs of a revolution?

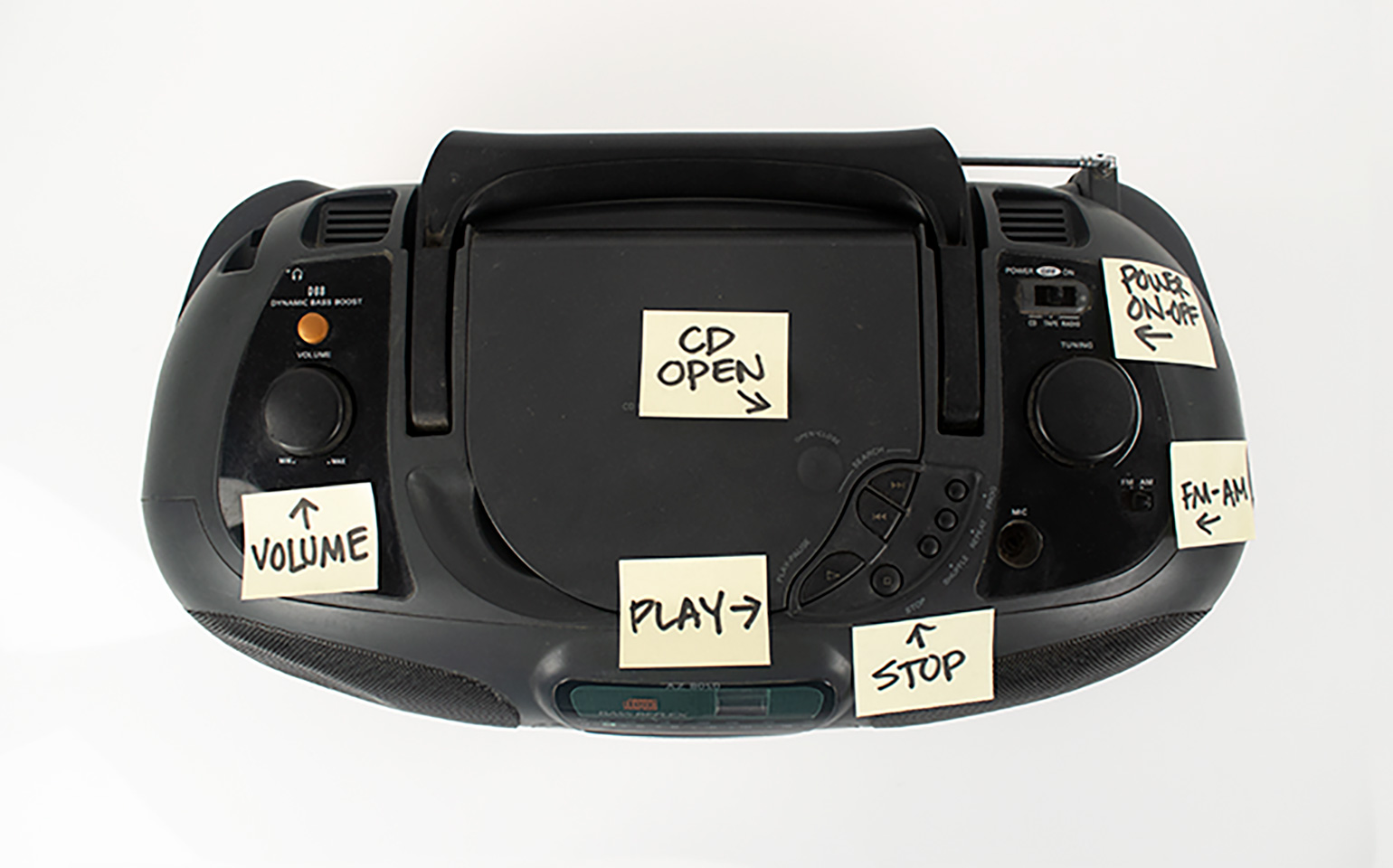

High-impact evolutionary innovation starts with market insight of trends, human behavior, and the user experience. The focus is on your current product. A new technology may also be in the mix, but new technologies and materials alone won’t cut it. The trick is making sure the new product has a distinctive design and an obvious, valuable improvement to users. Here are some examples of methods that work.

1. Leverage an Innovative (and Tested) Technology in a Distinctive Way

Jacobsen was the first in its category to use hybrid battery / gas engines for golf course vehicles. Hybrid engines were certainly not new—car manufacturers had used the technology for years. But Jacobsen’s application of the technology to evolve their product resulted in one of their most successful introductions ever. Jacobsen partnered with an experienced hybrid engine vendor to reduce the R+D costs and complications. The obvious benefit of a hybrid engine was reduced emissions and better fuel economy. But the electric system was better too. It was quieter, important for 5:00 am mowing past country club members’ homes. Also, the electric control system replaced hydraulics that tended to leak caustic fluids on the greens. The product’s success wasn’t just about hybrid technology. Jacobsen invested in industrial design to send the message that this was something truly new. They invested in a human factors study to improve the usability and safety of the cab—knowing that even though the drivers don’t purchase the vehicle they influence the people who do. And they did research with customers and users to gain empathy with their global market. The result is not revolutionary. But it is distinctive. In design, in overall user experience, and highly valuable since it reduces fuel costs and improves performance.