In the real world, people are diverse. Real people have varying abilities, appearances, sizes, and backgrounds.

But in the fake world, everyone is pretty much the same, pretty much like … me. In the fake world, everyone can read drug labels without glasses, lift a milk jug from a high grocery shelf, walk down the aisle of a commuter jet, climb up the playground structure at a city park, and access clean water from their tap.

Problem is, we still design for the fake world. Drug labels require magnifiers, grocery shelves are stocked high and heavy, commuter jets and skinny jeans are designed around the same legs, playgrounds marginalize kids with disabilities, and many people lack access to clean water.

Design for the fake world is perfect, simple, and exclusive.

Design for the real world is messy, nuanced, and inclusive.

Here’s what I mean….

A Very Brief History of Inclusive Design

The ADA

In 1990 president George H. W. Bush signed into law the American with Disabilities Act preventing discrimination based on disability and commencing design guidelines to ensure accessibility. It ushered in all kinds of design adaptations and accommodations. It was a wonderful achievement, and did in fact lead to accessibility, but not inclusion.

Universal Design

Around that same time Ron Mace, a North Carolina architect who had polio as a child, and used a wheelchair and a ventilator, started using the term Universal Design. He made the case that the design of products and environments should be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, regardless of age, ability, or status in life, and without the need for adaptation or specialized design. A classic example of Universal Design is the door lever. Levers began to replace doorknobs in the 90s because levers are better for people with limited hand strength, for people with groceries in their hands, and for people without hands—in fact they’re better for all people. Mace founded the Center of Universal Design at North Carolina State University and published the 7 Principles of Universal Design—to this day the foundation of Universal Design practice.

Ron Mace consulted with BOLTGROUP on product design and I became an advocate of Universal Design—and still am. However, some people hear the term Universal Design and assume it’s a bridge too far—an elusive perfection that seeks to be universally better for everyone, but is inevitably flawed by compromises.

Inclusive Design

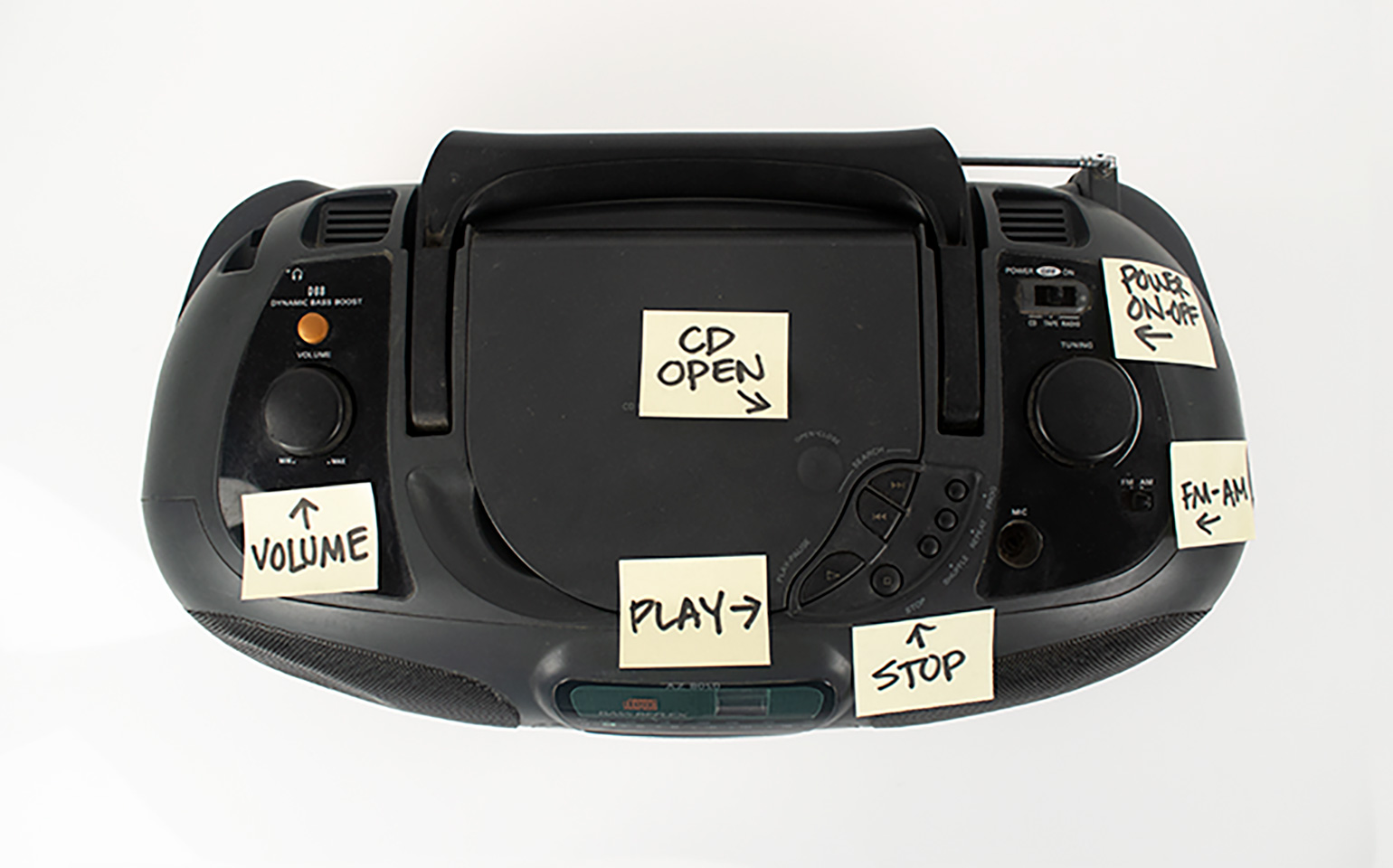

Inclusive design is less prescriptive, more affirmative, and more intentional in its advancement of diversity, inclusion, and integration. Inclusive Design considers the full range of human diversity with respect to ability, language, culture, gender, age, and other forms of human difference. Designing inclusively results in better experiences for everyone.** Inclusive design recognizes that people are different, and that sometimes, design needs to be different to meet everyone’s needs. And inclusive design doesn’t just “accommodate” diversity, it actively seeks diversity—gathering people of mixed perspectives, cultures, and abilities as part of design thinking and design output.

In recent years I’ve learned more about inclusive design. My eyes have been opened through personal experiences with clients, associates, family members, and employees. Here are a few examples:

Equipment Design

PlayCore is a manufacturer of playground equipment, and a leader in inclusive design for playgrounds. PlayCore hired BOLTGROUP to help create playground experiences that were not just accessible, but also inviting, appealing, and encouraging to the widest variety of kids—kids of all shapes and sizes, all abilities and needs, including children with wheelchairs and children with autism. The ADA established the minimums to make allowances and accommodations—but PlayCore and companies like it are going much further, seeking inclusion rather than just accommodation. The result of our joint design effort includes PlayCore’s Sensory Arch and Car Wash.