April 20th, 2017

Challenge the Status Quo Product Design Process

Some might say the BOLTGROUP design process is a bit odd. It’s an innovation process and a design process and a research process and a business framing process, all rolled into one. Odd or not, it works amazingly well.

5 Secrets of BOLTGROUP’S Design Process

1. Ask, What Is the True Need?

Clients who engage with a full-service design innovation firm like ours are usually adamant about what they need. However, sometimes what they think they need is not what they truly need.

The first step of an innovation and design process is to clarify the need and define the context of that need. Often the problem a client calls us about is not the actual problem that needs to be solved, but rather a symptom of the true problem. Clients know their business well, and most understand the big picture through intuition and analysis. So, together we take the first step of a good innovation process: we map out the big picture, the whole need, how the service project fits, and how they might address the rest of the story.

Some clients want new product ideas; some already have an idea and want a better embodiment of it. Some want new packaging, others want a new brand. But is what they want actually what they need? Our process helps clients walk through a self-reflection that guides them to the whole truth. It helps to step back and be able to see the root of the matter—the fundamental problem or big opportunity that will best meet their business goals.

Instead of new product ideas, they might need design language that pulls current products together in a cohesive system. Instead of a better look, they might need a better user interface, or a whole new idea. Rather than new packaging, the full answer might be a new brand strategy.

We call this first phase Framing the Need and Developing a Preliminary Strategy.

2. Make Discovery Research Iterative and Multidirectional…Just Like Design.

Iterative Research

This is a design methodology based on a cyclic process of prototyping, testing, analyzing, and refining a product or process. Much has been written about gaining empathy with the people who’ll use your products. Observing and interviewing the end user—truly walking in their shoes—has always been fundamental to our process.

But to develop a successful design strategy, you need more than just interviews and observations. You need a multi-pronged research method that builds knowledge through a series of interactions. A scientist continually expands a hypothesis through iterative testing and then uses that learning to inform the next step of research. Design is, of course, iterative too. During the design phases of a project, we create multiple ideas and get them in front of people for feedback, then develop better ideas based on what we learn.

Research works the same way. We’ll use one methodology—let’s say some primary research like user observation—to understand the most salient issues around a product or a brand. Next, armed with our knowledge of the big issues, we can generate good questions to ask customers. The kind of questions that make an interview, survey, or focus group relevant. Then we might conduct more ethnography, followed by a participatory design step where we inspire enthusiast users to generate their own ideas. Then another iteration of idea testing with more users to hone the final product design. A process of ever-greater discovery.

Also important is the new way we screen consumers for research studies. We now include the outliers to see where we might be headed—people such as the mis-user, the over-the-top enthusiast, the extreme DIYer, and the early adopter.

Beyond Empathy—Secondary Research

Primary research—where we’re speaking directly with the consumer—is not always enough. BOLTGROUP also invests in secondary research to look for mega trends, identify outliers, and find technologies that might aid the innovation. Sometimes we get to know the consumer better than they know themselves.

As David Epstein so aptly wrote, “Just because you’re a bird doesn’t mean you’re an ornithologist”. Being a Millennial doesn’t make you an expert on Millennials. Talking to a dozen Millennials may not give you the empathy and insights you need to explore the most meaningful innovations. But understanding them through a multifaceted blend of research methods just might.

Other Stakeholders

As designers, we see ourselves as an advocate for the end user. As such, our focus on the people who use the product is constant. It offers up the insights that lead to great design. Then again, the greatest discoveries, the biggest “Ahas”, can come from other sources. For example, some of the biggest finds exist in knowledge already held by our client, but are squirreled away in company lore or held secretly by staff.

Other discovery resources include: stakeholders within the manufacturing company, resellers, installers, and maintenance people. If installers or maintenance people hate the product, its marketplace growth will be stunted and no one will know why. That’s why we start our process with a series of broad interviews, asking the right questions in the right ways, then assembling that shared knowledge into a usable library.

We call this phase Blended Research.

3. See Future, Not Just Present, Needs.

In a recent white paper, Design Thinking Gets A Redesign, I described how the road to create world-class design and successful innovation starts, not just by meeting today’s customer needs, but with a vision of the future.

In an environment where changes in consumer attitudes, new technologies, or government regulations can reshape the business landscape, today’s design process includes tools to avoid upcoming potholes and leverage future opportunities. Real opportunity lies in understanding what people aspire to and how they’re likely to behave tomorrow. Several techniques make this possible, including participatory design sessions and future world visualizations based on market data. For more about that see my previous post.

We call this phase Envisioning the Future.

4. Perform Better Ideation for Bigger Connections.

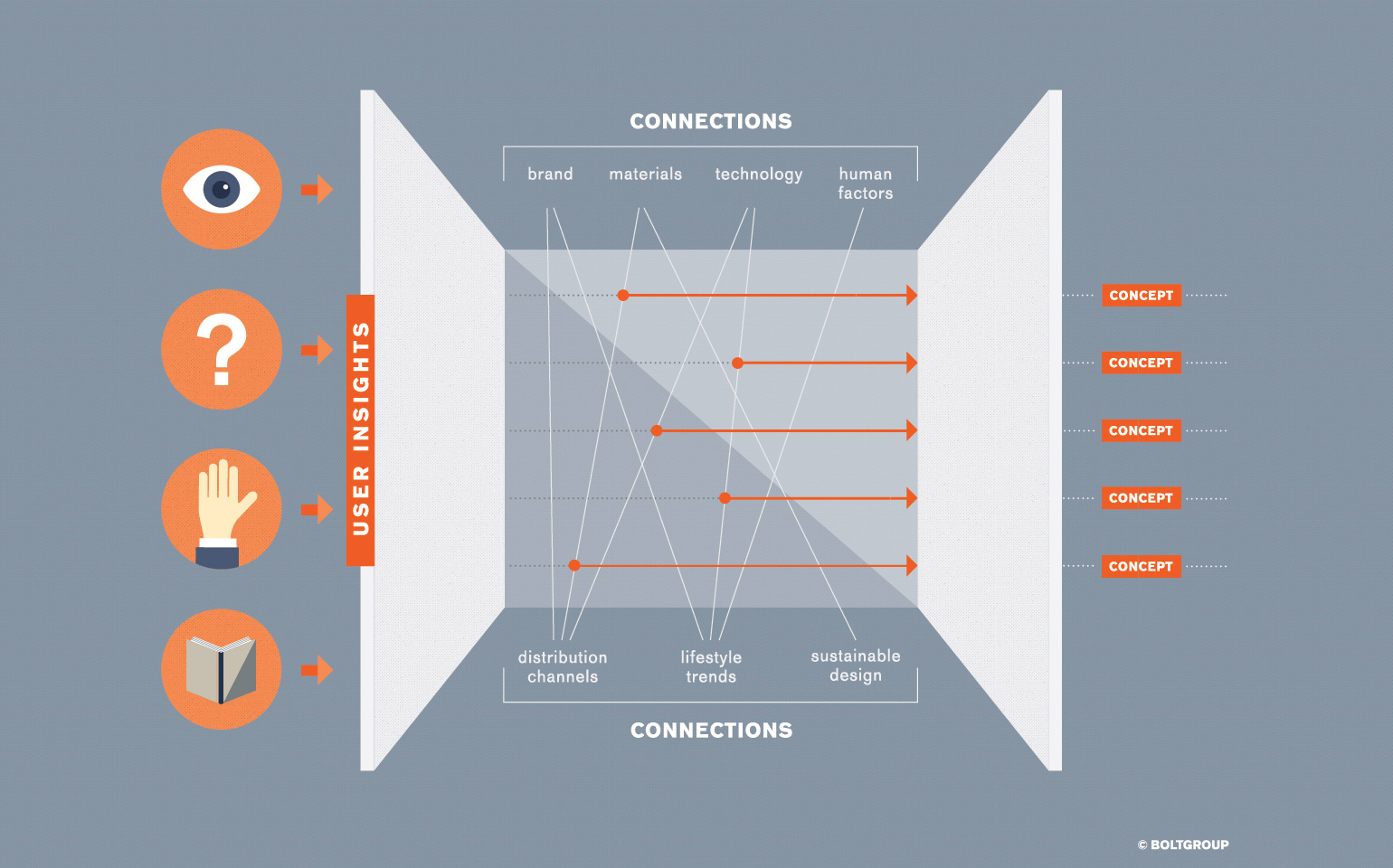

Ideas come from making connections. This may seem simple, but it’s not. Ideation, brainstorming, concept generation—these are all methods of making connections between things that previously seemed disconnected. As a creative firm, we use techniques that spur creative thinking and foster connections.

First, we recognize that some connections are made between disparate aspects of an issue. We look for connections between a user insight and a new engineering material, between a brand attribute and a product feature, between a need for sustainability and the human factor.

We appreciate how people work best. We understand where people fit within the continuum between concentration and collaboration—and we make sure to work both ends. Brainstorming is alternated with head-down, independent ideation. The back and forth between collaboration and concentration unleashes the best creative thought.

Sometimes collaboration / concentration is better in twos—two creative people in a friendly competition for the most compelling ideas. Sometimes it’s better in larger groups—shared ideas inspire other ideas. And sometimes it’s best individually—where deep thought focuses in on a thorny problem. At BOLTGROUP we do all three, and we do them with people from varied backgrounds to add spice to the idea soup.

It’s just as important to recognize when a topic area is “saturated”. Ideas dribbling out are no longer useful. That doesn’t mean we stop. Some of the best connections are made when it seems all known avenues have been explored. It’s just that we shift to another mode—from collaboration to concentration, from large group to competing duos.

We also recognize that “research” and “ideation” need not be separate modes of working. Through the iterative approach mentioned above, our research can feed ideation, then the ideation feeds the next step of research. And so on. Through participatory ideation, valuable ideas are tested out on consumers themselves. We combine participatory design sessions with skilled listening for inferences of what people are thinking. Then journey maps help us visualize patterns of experience, predicting future behavior given a similar situation. These techniques allow design to be more predictive and less reactive.

Lastly we practice “sketch ideation.” Designers use this technique to push creative thought through hand / mind / eye coordination. Here’s how it works.

When presented with a design goal—say a better potato peeler—designers ideate through sketching. Sometimes a line drawn on the page precedes the idea in the mind. The quick, artfully drawn sketch of a curved blade or an ergonomic shape feeds the designer with more ideas. It’s iterative—the lines on the page, then the designer’s cognition of how that line might evolve, then more lines and shading, then “Aha”! The designer sees something new on the page, something unexpected yet cool! The line becomes form, the form becomes an idea, the idea leads to the next form, and on it goes.

With this skill, designers generate many product concepts that find their way into mockups and testing with consumers.

We call this phase Making Connections.

5. See It Through. It’s Not Innovation If There’s No Adoption.

Some years ago I was interviewed for a podcast by a national business magazine. The interviewer asked me how I defined innovation. I told him that innovation is a novel idea that provides value to someone. Now I’d clarify that to say it’s a novel idea that comes to fruition and provides value. The point is that, without coming to fruition and providing value, it does not reach the status of innovation. And without adoption—without customers acquiring it, using it to their benefit, and recommending it to their friends—it hasn’t come to fruition and been given value. So a key part of the innovation process is adoption.

The process of design and innovation (design thinking) now includes design of the introduction and adoption. As I mentioned in my previous white paper, after an innovation is developed, its launch to the market and its acceptance by the consumer will determine success or failure. It’s what Roger Martin calls “intervention”—the integration of a new product or system into the status quo. Getting people to engage with, learn, and adopt new ideas is often the Achilles heel of innovation. But design process can be an important part of securing adoption.

An example of the importance of building adoption is the iPod. This little wonder has been called the “overnight success that took three years to happen”—Bill Buxton. After the iPod’s launch, Apple made numerous changes to the product that were essential to its eventual success. Many technology products employ this strategy—launch a simplified version to build user acceptance, but design the product platform to add more complex features as users gain familiarity and provide feedback.

The introduction of a new brand—plus its products and services—presents a keen intervention challenge. The adoption often falls short at the points of coaching within the organization, building alignment with disparate business units or sub-brands, or the coordinated rollout across the marketplace. A case in point is our experience designing, launching, and then relaunching the Kobalt brand of tools.

BOLTGROUP created the Kobalt brand for Lowe’s to fill the positioning gap between Craftsman and Snap-on—to be the best hand tool available at retail. Our process included consumer research to define brand attributes and value proposition, creation of the name Kobalt, and the complete brand identity, industrial design of the products, and packaging and merchandising design for the nationwide rollout across Lowe’s stores. The tools were outstanding. Made by Snap-on, they were, in fact, some of the best tools anywhere—despite the fact that Snap-on branding was very fine print on the packaging.

But within a year of introduction something was wrong. Lowe’s merchants, thrilled to have a compelling new brand, pasted Kobalt badges on everything from cheap bungee cords to imported toolboxes. The Kobalt brand had veered out of its lane and the premium brand position we created had been compromised. Consumers didn’t believe Kobalt tools were worth their premium price, so they weren’t buying. While the initial introduction appeared successful, adoption was slow and sales were lackluster. Lowe’s called us back in to help.

We became the defacto Kobalt brand stewards for the next two years. We reined in the product categories where the brand would appear and tightened up the visual brand language to clarify the premium position. We conducted a six-month brand ambassador tour to build ties with shade tree mechanics, car magazines, and NASCAR. Also, we helped Lowe’s with training aids for sales associates, coaching them to ask customers, “Did you know this tool is made by Snap-on?!” Kobalt soon found its wings. Adoption skyrocketed and the brand is now Lowe’s most successful brand, and one of the biggest store brands in the world.

So here they are again, the five new twists to the design / innovation game:

- Clarify the need and define the context of that need to learn the full opportunity.

- Use multi-pronged insights research, blending different methodologies and looping through iterations that include research, ideation, testing, and more research to go beyond baseline empathy.

- Consider future needs, not just present realities to future-guard your business.

- Expand the ideation process and focus on connections to generate the best solutions.

- Design the launch and the adoption to improve success of your “intervention” into the market.