In 1978 Heinz Ketchup created a spin marketing campaign. The fact that their thick ketchup took so long to pour from the bottle was repositioned as a plus, and they used the Carly Simon song “Anticipation” to make the point. The problem was, the user experience never quite matched the advertising. Yes, we anticipated it alright … sometimes waiting for minutes, shaking the bottle, poking it with a knife, slapping it in just the right spot.…until it finally gushed out, covering the plate. The product experience was a negative. Twenty years later Heinz got smart. Rather than spin a negative experience as a positive they decided to design a new experience. Their squeezable-plastic-upside-down-bottle affords ketchup lovers the great experience they crave. The ketchup is always right at the opening, it comes out faster, and the pin in the lid keeps the dried ketchup crust from building up. For the user it closed a gap in the positive experience with the Heinz product and brand. For Heinz the plastic bottle led to increased ketchup sales.

Today when we think of designing the user experience, it’s often focused on the interactions people have with a digital screen. The design of screen graphics, navigations, buttons, and gestures form the experiences that get keen attention. That’s not a bad thing, but it’s only part of the experience. The total experience involves a much broader environment. Like an architectural environment, our experience with a product is the summary of each touchpoint, each stop along the journey with a product. The aesthetic, kinesthetic, tactile, intellectual, and emotional components of the experience all play a role. What’s more, our experience is driven not only by the product, but also by our motivations and emotions, and by the brand we perceive surrounding the product.

In truth, we can’t exactly design experiences. Only people can bring the emotions, memories and perceptual skills needed to activate human experience. But we can design the catalyst for experience and the opportunity to make the experience wonderful.

As a product designer working in both the digital and physical realms, I like to look at other professions for ideas on how to create the catalyst for positive experiences.

Here are three…

1. Product Design as Method Acting

What’s My Motivation?

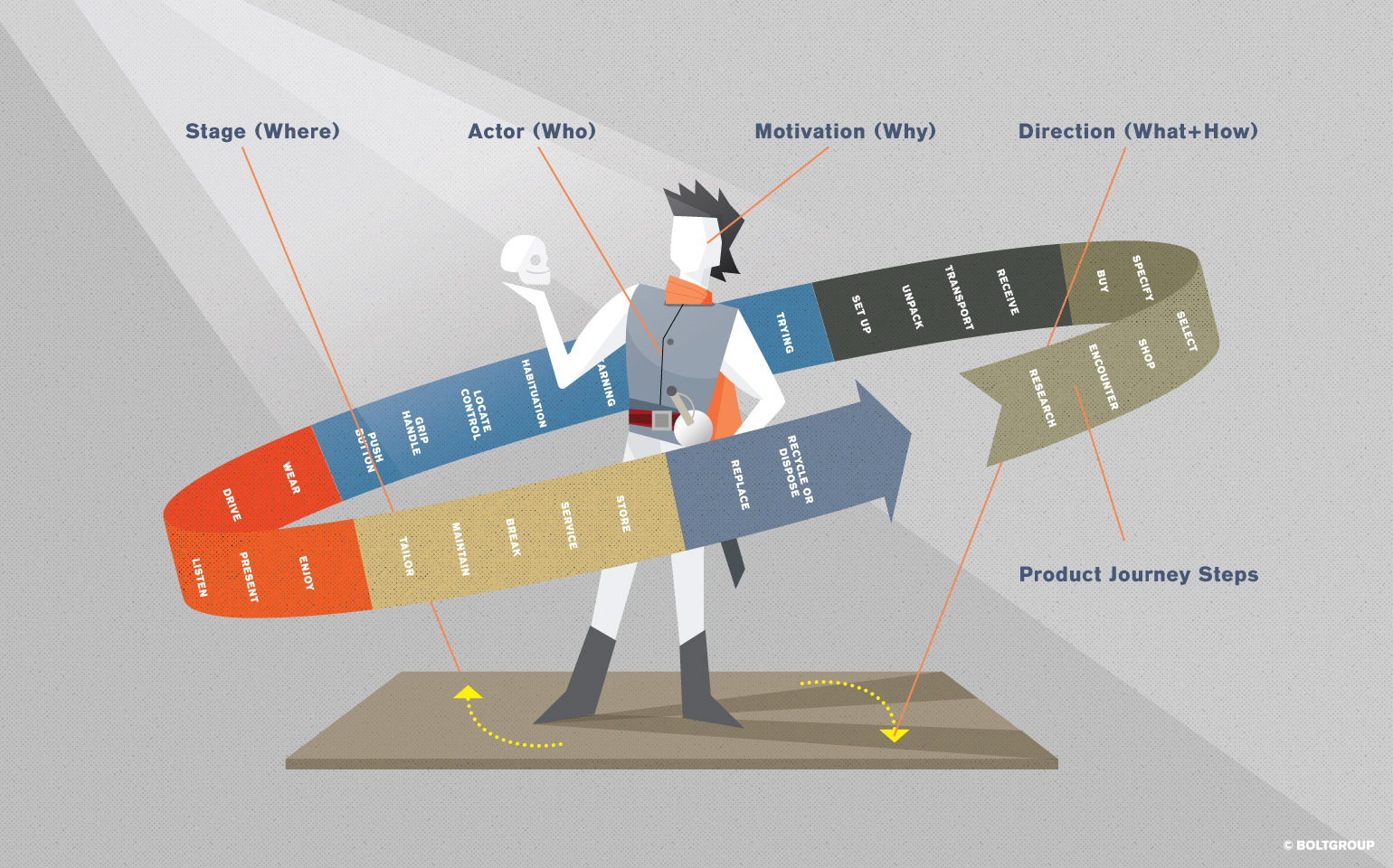

A deep dive into the Who, What, How, Where, and Why of people’s interactions with a product leads to a better understanding of the total experience. By dissecting each of these facets we see the impacts they have. And by looking at them through the lens of an actor we can get at the essence of “Why.”

Who

First ask Who will activate this experience. In business we often call them users, consumers, or customers. But really they’re people, guests, or audience members. What do they bring to the table? What do we know about their needs, desires, attitudes, emotions, capabilities, and preferences? Since we started our design business in the 1980s, we have dedicated the first phase of each project to gaining empathy with the people who’ll use the things we design. We’ve written extensively on ways to gain that empathy (see more at this article).

What

What is the activity people wish to accomplish? Cleaning the floor, making a phone call, blending a breakfast smoothie. The What helps determine the prioritization of features and steps in the physical and digital interaction with a product.

How

Through the How we accomplish the What. The How defines the series of operational and sensory interactions that take place between the person and the object. Things like pushing the buttons, pulling the handle, navigating the menu, or swiping the screen.

Where

The Where is the environment in which the experience with a product takes place. While some products are site-specific (a doorknob, a glove box) and others live in a variety of environments, the environment of use impacts all product experiences.

Product design often stops here. The Who / What / How / Where often makes up the “problem-solution” in a design project. But this ignores the essential Why.

Why

If the user experience were a performance, the Who is the character, the What is the action, the How is the script, and the Where is the scene … then the Why is the motivation—hugely important! Method actors like Marlon Brando and Dustin Hoffman looked for the underlying motivations of their characters to channel authentic emotions. They wanted not to “act” but to react to the situation with true feelings.

Product designers can uncover insights that lead to positive experiences by looking at motivations—the needs, emotions, and feelings that drive a person to interact with a product. I use a vacuum not just to get dirt off the floor, but to impress someone, to feel better about myself, or to feel like I’m keeping my family healthy. We make a phone call to connect, share, learn, or vent. We come to our morning smoothie blender worried about the day ahead, feeling like we need a healthier diet, but too rushed to cook something more. Examining the characters in the performance, their actions within the scene, and most importantly, their motivations, provides designers with guidance towards better experiences.

2. Product Design as Architecture of an Immersive Environment

Creating the Journey

Early in my career I designed experiential environments, like hands-on science museums and corporate showrooms. We created places where people combined learning and play to have delightful, enriching experiences. Our design touched every facet of the experience: the aesthetics of the architectural spaces, the sounds and lights guiding people through, the structure and graphics of hands-on exhibits, and the naming and branding of the business. Our design process included a “visitor experience map”—a diagram showing every encounter the visitor might have with the museum and its exhibits. The map was a series of concentric rings. At its core was the sequence of interior spaces and exhibits. The next ring was the museum exterior including arrival, parking, and approach. And finally, an outer layer showed the museum’s brand and public communications (back then we called it the “identity”). Nowadays this diagram of experiences might be called a Journey Map. Using a journey map in product design, like my experience map through an immersive environment, can give product designers food for thought as they create more encompassing experiences.

The Journey Map—Diagramming Interactions

Unlike my experience map, journey maps today are usually focused on navigation through a website or a building. But the same customer journey holds true for the total experience of a product.

A journey through the life of a product is a series of stopping points with transitions between. As product designers we study each point—every environment of use, every moment, every touchpoint. We seek to understand the user’s objective behavior and their underlying motivations. For each interaction we consider the user’s Actions, Thinking, and Feelings. Actions can be observed through research. Thinking and feelings can be inferred or sometimes learned through interviews. We also consider the journey through the purchase process so we can build visual cues into the product design that communicate the right messages at the point of sale.

A typical product journey might look like this….